By Lilly Bianco, Assistant Planner + Preservation Specialist at M-Group

Historic preservation’s roots go back centuries and while the major tenets have remained the same, the field of preservation has evolved such that the discipline is changing in fundamental ways. For the past century historic preservation activities remained largely confined to landmark structures and those associated with the great men of our past (yes, mainly men). The initial impetus for historic preservation showed a rather profound undercurrent of subjectivity and aesthetic idealism that only really began to dissipate within the last thirty years. Since the 1980s the discipline of historic preservation has begun to take a much more holistic and integrated approach, thanks to ideas conceptualized by cultural geographers in the early twentieth century. The concept of “cultural landscape” is changing not only how we preserve, but also what we preserve.

Bodie State Historic Park, CA (Former mining town and Vernacular Landscape). Photo Courtesy of parks.ca.gov

The concept of cultural landscape developed serendipitously through the parallel discourse in anthropology, landscape architecture, cultural geography and history. Cultural geographer Carl Sauer coined the term, “cultural landscape” in 1925 and explained it in the following terms; “culture is the agent; the natural area is the medium; the cultural landscape the result.” This explanation illustrates the rather broad nature of the concept; it is not, as is often believed, synonymous with a “designed landscape” which refers to a formal garden, suburb, plaza, boulevard, or park. Rather, a “designed landscape” is but one type of cultural landscape.

Balboa Park, San Diego (Designed Landscape). Photo Courtesy of TCLF.com

The National Park Service recognizes four types of cultural landscapes which are not mutually exclusive:

- Historic Site - (a site associated with landmark event or figure;)

- Historic Designed Landscape (park, garden, cemetery, institutional grounds, suburb, boulevard);

- Historic Vernacular Landscape (a cultural landscape that has developed organically, e.g. a rural farm, cultural route, industrial complex); and

- Ethnographic Landscape (a cultural landscape containing resources that associated people define as heritage resources).

Cultural landscapes are complex and unique and can vary widely in scale – it could involve a historic five-acre farm and historic and cultural resources therein; or it could encompass the entire historic urban core of a City. Pictures or representative examples of protected cultural landscapes are shown throughout this article.

A portion of historic Oregon Trail, (Vernacular Landscape), Photo Courtesy of post-gazette.com

All of these cultural landscapes are understood through the lens of “landscape characteristics” which refers to the tangible and intangible elements within the cultural landscape that contribute both singularly and cumulatively to its significance and aid in defining its unique character. Landscape characteristics, as defined by the National Park Service, include the following elements: Natural Systems and Features, Spatial Organization, Land Use, Cultural Traditions, Cluster Arrangement, Circulation, Topography, Vegetation, Buildings and Structures, Views and Vistas, Constructed Water Features, Small-scale Features, and Archeological Sites. Beyond the value of the singular landscape characteristics is the holistic value, whereby a place can be understood through the larger patterns and relationships between what, at first glance, appear to be disparate pieces.

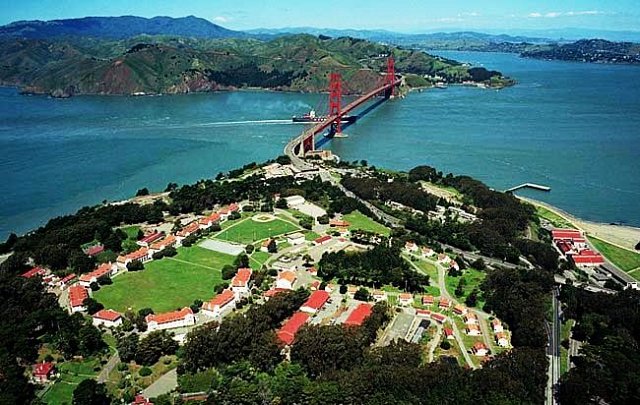

San Francisco Presidio (Historic Site/ Designed landscape). Photo Courtesy of sf. Funcheap.com

Recognition of this concept has encouraged a broader view of what constitutes a resource, meaning that no longer are we inclined to just preserve the plantation house, but also the outbuildings, the former slave’s quarters, the spatial organization of the row crops, the lone cedar that delineates the family burial site and the view shed as seen from the second story porch. The holistic approach allows for a broader and more complete interpretation of place. The cultural landscape approach has further encouraged an increasingly broad array of resources to preserve as greater consideration is given to those resources that explain who we are rather than those that are simply aesthetically pleasing or denote landmark events — industrial heritage, agricultural landscapes, vernacular resources, urban landscapes, highways, traditional cultural properties and cultural routes have all garnered much deserved attention that was mostly absent prior to the 1980s.

Faubourg Treme neighborhood, New Orleans (Ethnographic Landscape, Vernacular Landscape, Designed Landscape, and Historic Site). Photo Courtesy of AmericanBluesScene.com

While the cultural landscape approach to preservation has gained momentum there remain numerous opportunities to improve our efforts and better integrate the concept into our everyday planning activities. These opportunities can be found in the potential for more concerted efforts at cross-disciplinary and cross-jurisdictional cooperation; further integration of preservation into sustainability initiatives, and of course improved educational initiatives to inform planners, communities and stakeholders. The integration of the Cultural landscape Concept into planning means more effective preservation that is both more valuable and more relevant. For further reading on the topic I recommend:

- Cultural Landscapes: Balancing Nature and Heritage in Preservation Practice, Richard Longstreth, Editor.

- Managing Cultural Landscapes, Edited by Ken Taylor and Jane Lennon

- NPS Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes http://www.nps.gov/tps/standards/four-treatments/landscape-guidelines/

- UNESCO Cultural Landscape http://whc.unesco.org/en/culturallandscape/

Sources Referenced:

- California Parks Cultural Landscapes and Corridors. http://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=22854

- Longstreth, Richard. Ed., Cultural Landscapes: Balancing Nature and Heritage in Preservation Practice, (The University of Minnesota Press: University of Minnesota Regents, 2008)

- Page, Robert, and Cathy A. Gilbert, et al, A Guide to Cultural Landscape Reports: Contents, Process and techniques, by U.S Department of The Interior, National Park Service, Cultural Resource and Stewardship Partnerships, Park Historic Structures and Cultural Landscapes Program, Washington DC, 1998.